Health Facility and Household Survey on Access to and Use of Medicines in the Philippines

Research Project Terminal Report

Title: Health Facility and Household Survey on Access to and Use of Medicines in the Philippines

Implementing Agency: Institute of Philippine Culture – Ateneo de Manila University

Funding Agency: Department of Health and Philippine Council for Health Research and Development

Project Staff: Dennis B. Batangan, M.D., M.Sc. (Heidelberg), Leslie V. Advincula-Lopez, Ph.D., John Paulo C. Dalupang, M.Sc.

Executive Summary

The facility and household survey was conducted in 2017 with funds provided by the Department of Health (DOH), coursed through the Philippine Council on Health Research and Development (PCHRD). This survey aims to provide inputs for the DOH to come up with policies that would make medicines more accessible to the Filipinos, and also, to understand the rationality (or lack thereof) in the use of medicines at the household level. The WHO protocol for the Pharmaceutical Situation Assessment, Level II and Level III, was adopted as the methodology for this study.

The indicators in the survey measure the outcome and impact of strategic pharmaceutical programs in a country: improved access, quality and rational use. Access is measured in terms of the availability and affordability of essential medicines, especially to the poor and in the public sector. Measuring the actual quality of medicines by testing samples can be expensive. Instead, the presence of expired medicines on pharmacy shelves, as well as the adequate handling and conservation conditions, are indicators of the quality of medicines made available to the population. Availability of prices of innovator and generic medicines at the public procurement, public sector and private sector sources were studied in the survey. Finally, rational use is measured by examining the prescribing and dispensing habits of health providers and the implementation of key strategies such as standard treatment guidelines (STG) and essential medicines lists (EML).

The study was conducted in six (6) survey areas, consisting of one (1) major city and five (5) provinces. The survey areas include: La Union Province in Region 1; Pampanga Province in Region III, City of Manila in the National Capital Region, Palawan Province in Region IV-B; Capiz Province in Region VI and Misamis Oriental Province in Region X. In each survey area, the sample of public facilities was identified by first selecting the main public hospital, and a primary/rural health center or lowest level public health facility. An additional six public facilities per survey area were then selected at random from all middle level public health care facilities, except in Palawan Province where only six (6) middle level public health 11 care facilities were surveyed. Eight private health facilities were originally targeted per geographic site. However, only five (5) from Capiz and Palawan, respectively, and seven (7) from La Union were included in the study. Meanwhile, twelve private pharmacies per area were included in the study except in Palawan where only four (4) pharmacies participated in the study. In all study sites, one regional or provincial warehouse that supplies the public sector was visited. The study also had some problems accessing health NGOs, With the exception of Metro Manila where four (4) health NGO were interviewed, no health NGOs or mission hospital was available in the other five (5) project sites. Overall, 46 public health facilities, 41 private health facilities, 64 private pharmacies, four (4) health NGOs, and six (6) warehouse were included in the study.

The survey was designed to provide a picture of the pharmaceutical situation in a country. The sample sizes used however were statistically not large enough to make inter-facility comparisons. Regional comparisons should be done sparingly as not all geographic regions are represented and over-emphasizing the six regions included in the study may detract focus from the study’s significance as a national survey.

The highlights of the 2017 PSA include the following:

– The findings on the access to medicines show that key essential medicines selected for the country are partially available in public health facilities (69%), warehouses that supply public health system (74%) and private pharmacies (63%). The length of stock out durations at the public procurement (69 days) and public sector (63 days) indicate that the key essential medicines are not continuously available. These figures reflect some inefficiencies in the public health system procurement and distribution. The public sector procurement and distribution system needs to be reviewed and enhanced to increase availability and access to key essential medicines 12

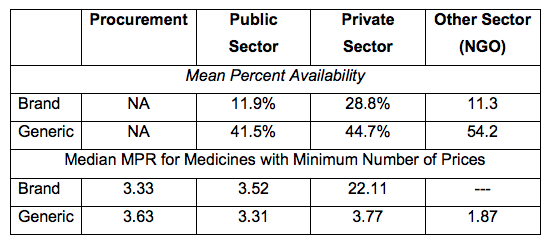

– From the global list of drugs, mean availability of originator brand and generic medicines in the public sector was 12 % (compared to 8% in 2009) and 42% (27% in 2009), while in private sector it was 29% (14.7% in 2009) and 45% (20% in 2009), respectively. This indicates a huge jump in the availability in both the public and private sector outlets but more in the private sector. Mean availability of generic medicines in other sectors (or NGOs) was very high at 59%. However, there are very few (4) such outlets included in this round of the survey. The overall picture indicates that generic medicines have become more available in the public and private sector outlets but more in the private sector.

Availability and Median MPR of Selected Medicines in Different Sectors

– The public procurement has been shown in the 2005, 2009 and 2017 surveys to have the lowest MPRs for generic and innovator brands. However, in 2017, it is still purchasing medicines at prices higher than international reference prices (3.33 for branded medicines and 3.63 for generic medicines). Public sector patient prices, on the other hand, decreased significantly from 30.23 (2009) to 3.52 for innovator brands, and from 9.78 (2009) to 3.31 for generic medicines. A separate study can be designed to identify the factors contributing to this decline in prices.

– In the public sector, the procurement agency has been shown to have the lowest MPRs but is purchasing medicines at prices higher than international 13 reference prices (3.33 for branded medicines and 3.63 for generic medicines), indicating a relatively fair level of purchasing efficiency. These can be improved further to increase availability of generic medicines sold at a lower price in the public sector outlets.

The table below shows the trends in medicine prices using the Median Medicine Price Ratios (MPR) as reference in studies conducted in 2002, 2005, 2009 and 2017.

* Health Action Information Network (HAIN), 2002

** Institute of Philippine Culture, Ateneo De Manila University (IPC, ADMU), 2005

*** People Managed Health Services Cooperative (PMHSMPC), 2009 14

**** Institute of Philippine Culture, Ateneo De Manila University (IPC, ADMU), 2018

– From the household survey, the average monthly cost of medications for chronic disease was PhP 1166. The average cost of a prescription for acute illness was PhP 517. Generic medicines are perceived to be less expensive compared with branded medicines. Most frequent reasons for noncompliance to medical treatment for acute and chronic diseases were improvement of symptoms, advice from someone in the household against completion of the course, and unaffordable medicines. Medicines covered by insurance for acute and chronic conditions were very negligible.

– Affordability of medicines for certain disease conditions and treatment, defined as the number of days’ wages of the lowest paid government worker needed to purchase standard treatments, are the same for lowest price generics in the public and private sector outlets. Some conditions are: adult Pneumonia [Amoxicillin] (0.2 days) and Hypertension [Captopril] (0.6 days). The affordability of lowest priced generics in the public sector improved but most conditions would still require at least half a day’s wage. Treatments costing over a day’s wage of the lowest paid government worker was limited to adult Pneumonia [Cefuroxime] (1.3 days).

– Less than half of all the prescriptions for acute and chronic illnesses were from medical professionals with high prevalence of self-medication among the respondents. This pattern was reported for acute illnesses where the proportion of what looks to be minor illnesses (runny nose etc.) is high, which may further reinforce this observed trend. Furthermore, most of the medicines found at home were from past treatment regimen.

The EML and the Standard Treatment Guidelines (STG) were found in 73% and 67% of the public healthcare facilities, respectively. This indicates that there is still a need to promote vigorously the importance of having a copy of both EML and STG in all public health facilities. 15

– The average number of medicines per prescription at the public facility dispensaries was 2.0 and can be considered adequate. The percentage of patients with antibiotics prescribed in the public facilities was 53 %. While a little lower than the 63% in the 2009 health facility survey, this figure is still considered high, and may indicate an irrational prescribing pattern for this group of medicines. The percentage of patients with prescribed injections from public facilities was 7%. This is considered an adequate prescribing pattern for this group of medicines.

– Another variable studied was the adherence of prescribers to recommended treatment regimens. Findings show that prescribers are likely not to adhere to treatment guidelines. Forty percent (40%) of non-bacterial cases of diarrhea were prescribed with antibiotics, 70% of non -pneumonia ARI and 60% of those with mild/moderate pneumonia were also prescribed with antibiotics.

– The median percentage of prescribed medicines that are on the national Essential Medicines List (EML) was 50%, indicating a somewhat limited adherence of physicians to this list. However, 100% of medicines included in the survey were prescribed using its generic name. This pattern suggests better access to medicines and rational use.

– The percentage of medicines adequately labeled was 100%, for both public health facility dispensaries and at private pharmacies. Patients at both private pharmacies and public health facility dispensaries knew how to take their medicines. Both facilities registered 100 median percentage for this indicator.

Recognizing that many of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were not met, 195 countries including the Philippines adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) for 2016 to 2030, to replace MDGs. The health-specific agenda, SDG No. 3 states ʺEnsure healthy lives and promote well-being for all of all ages.” The 16 Philippines Health Agenda 2016-2022: All for Health towards Health for All, is the blueprint of the current administration to attain this health-related SDG. More recently, the DOH also revitalized the FOURmula 1 program, now called FOURmula 1+, which aims to boost universal healthcare delivery through improved a performance governance system (DOH, 2017). Specifically, target number 8 of SDG No. 3 aims to achieve universal health coverage (UHC) including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health care services & access to safe, effective quality, & affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.

While the existing programs on rational medicines use, including health access to cheaper and better-quality medicines are apt articulation of SDG No. 3, the inaccessible and prohibitive health costs in the country remains a major issue. The results of this study showed that the mean percent availability is higher for generic medicines (42% for the public sector and 45% for the private sector) compared with the branded medicines (12% for the public sector and 15% for the private sector). The highest mean percent availability figure in the study was 45% for generic medicines in the private sector. Using the same methodology for measuring availability of essential medicines in 2009 and 2017, the current study showed that generic medicines availability in the public sector increased from 27.5% (2009) to 42% (2017) while branded medicines availability also increased from 8 % (2009) to 12% (2017). These figures, however, are still below the 2003 MDG report estimate of 50-70% and 2004 WHO estimate of 66% on the indicator “proportion of the population with access to affordable essential medicines.” Further, it is interesting to note that availability of medicines for both branded and generic brands are higher for the private sector, and though it may not be statistically significant, the pattern is worth exploring further.

The results of this survey show that on the sample considered, availability of basic medicines is still an issue. Relative to the 2009 results, medicine prices do not look as high now when compared with international reference price, as well as, to the poorest consumers’ ability to pay for it. However, in a country where a significant portion of the population are considered poor (22% in 2015) paying three times more than the international price is still a major concern. While programs on 17 medicine access and health insurance coverage have expanded tremendously in the last few years, there is still a need to validate whether the assistance are really reaching those who need it most. In a context where many outpatient medicines are not covered by the national health insurance, and where client targeting is still an issue, price determinant can further exacerbate existing barriers to medicine access. The results from the household survey also has the same conclusion.

Click for Full Project Terminal Report